Audio en français >>>

Audio en español >>>

Présenté à l’exposition collective LE SEPTIÈME PÉTALE D’UNE TULIPE-MONSTRE (25 janvier-26 mars 2023) à la Galerie d’art Louise-et-Reuben-Cohen, Moncton, NB.

Commissaire Elise Anne LaPlante

English Version. Translation by Simon Brown

Coffee Breath: A Treatise on Watercolours and Coffee

by an Elephant Woman

One day, in 2015, I was given a special mission. This came about thanks to a social-media intercession on the part of the Corazón Desfasado. The Corazón Desfasado was the first character I created with the goal of speaking to the migratory experience in Montreal from the perspective of my own body, a woman’s body formed in and by the Colombian Carribean. The Corazón Desfasado is a fictional saint who was born from invented relics, miraculous performances, and collages splicing together Catholic prayers and advertising slogans. Two years following her initial appearance on Facebook, the Corazón Desfasado’s account was reported for use of a fake name, and suspended. This account had been dedicated to fighting the perversions of hypercapitalism, particularly by calling out censorship of artworks, advocating for anti-racist and feminist causes, and highlighting the noisy violence of gentrification, with its excavators and jackhammers in the alleyways of my neighbourhood.

For each supplication received by the Corazón Desfasado, I try to think ahead, and properly evaluate the response. But it’s always something of a disaster. On this particular occasion, a Facebook “friend”—a woman also originally from Central America who I didn’t know personally—had asked me to make a version of the “planet of breasts” vest adapted to her dark-brown skin colour. I tried my best. I adjusted the colour of the original piece in Photoshop, but the result seemed bland, and even opportunistic. Then I attempted to make new watercolour versions based on examples of darker skin tones on my computer screen. However, I quickly realized that flat internet images couldn’t possibly serve as reliable points of reference. So, following several failed attempts, I gave up. The Corazón Desfasado wouldn’t be able to answer this supplication.

Four years later, I was invited to an artist residency in Baltimore. Like my hometown Cartagena, Baltimore is a port city whose history is marked by racial tension, exploitation, and poverty. Given my own experience of growing up in a colonial context, my time in Baltimore reminded me that our bodies are constantly being traversed by hate and violence in their many racist, classist, and misogynistic forms. I couldn’t help making the connection between the two cities. In the project I began during this residency, Pigments sauvages (2019), I again tried to take up the challenge my Facebook friend had initiated. In so doing, I was to tackle the question of racialization in my work for the first time.

Arriving in Baltimore with the first warm days of spring, I let myself be enchanted by the twisted forms of the trees awakened by the balmy March weather. Their trunks showcased a surprising range of colours, from brown to purple and green, to a whole gamut of greys, from light to dark. In the bark of these trees, I believed I could make out a poetic clue that might show me how to approach the diversity of skin pigmentation in a new way. I found the results disturbing. The first images were of visibly sick breasts: the shades of grey, purple and brown definitely evoked cancer.

Watercolours and illness.

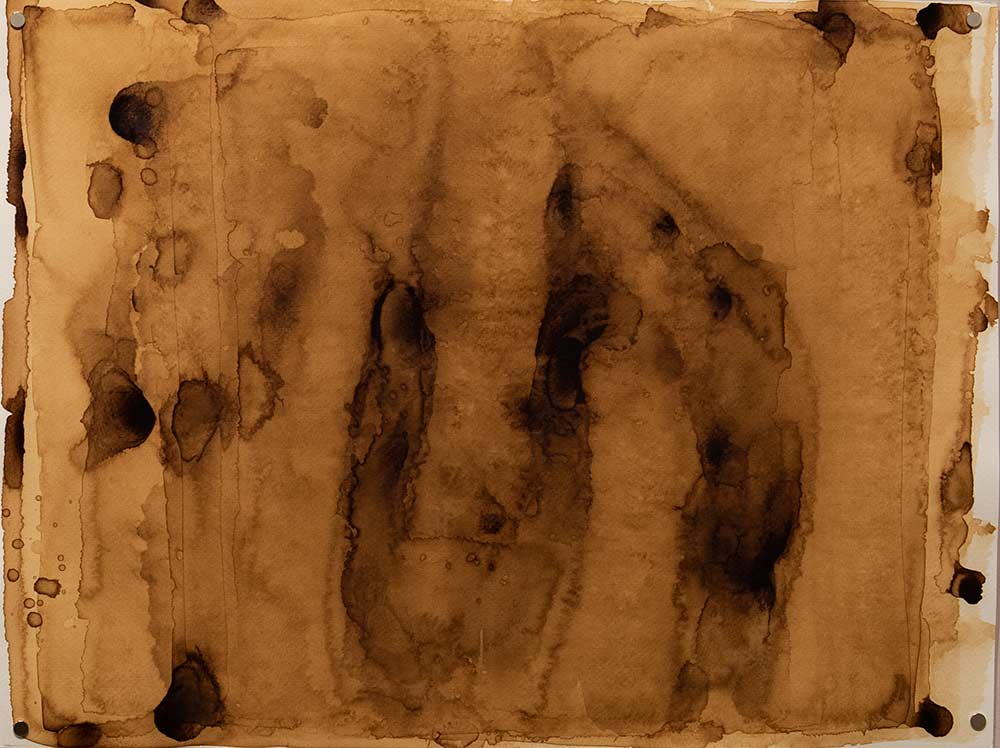

When it comes to representing the body, I sometimes let myself be guided and surprised by technique, while always trying to prioritize care and attention at the same time. I’ve used this approach in several projects, including Étude pour habiller une femme éléphant (2011), Fronteras (2014), and Nuancer (2019), where I played with possibilities stemming from a dialogue between technique, material and artistic intention. Sometimes, depending on the quality of the paper and the proportion of water to pigment, watercolour paint leaves stains that resemble aureoles. In French, these stains are called cernes, or rings: there is a higher concentration of pigment around the edge of the coloured puddles, thus creating darkly outlined clouds upon evaporating. To avoid these rings, the artist must plan ahead, tilting the paper, and rubbing dry the outlines with the tip of the brush. Or, she can accept the vicissitudes of technique. Watercolour painting indeed demands either a particular attentiveness in order to properly manoeuvre the brush, or a total surrender to the whims of the medium. One day, a friend surprised and destabilized me with his reading of these works. For him (a historian of religions) these aureoles seemed to suggest diseased skin. All this reminded me of my own dermatological problems as a teenager. In retrospect, I think it was a way for my body to express the anxiety stemming from the violence all around me. The girl I was grew up bewildered in a city poisoned by hypercatholicism, social divides, and poverty: a toxic mix produced by tradition, corruption, and inequality. I was plagued by hives, infections, rashes. Colonized as it was by confinement and fear, tiny lesions broke out routinely almost all over my body: on my hands, feet, abdomen, back, knees, and thighs.

Now aware of other possible readings of these pigmented rings, my point of view has broadened: on the one hand, I like the pictoriality of the images; on the other, I understand that they indeed have the potential to evoke illness. What an odd tension between the quest for beauty, with all the subjectivity it implies, and horror, disease, decay, and death! One might even say that beauty and horror go hand in hand. Nothing new under the sun! I read similar observations long ago, in an essay on the sublime in 18th-century art.

I’m starting to become aware that I talk about death and violence quite a lot in my practice, albeit indirectly, like a transparent layer, or the thrum of a distant motor somewhere behind the scenes. The more we keep our wounds open, the more we examine and play with them, the more exhausted we become. I now realize I have to accept the fact that violence is an inescapable theme in the creative process, whether it be in an elephant woman’s studio, or in her bedroom.

I return to the paper to continue my search for approaches that might allow me to properly represent bodies of colour, that is, without rushing, and without resorting to clichés. Here, I think it’s important to specify that the initial version of Planète des seins was, on the contrary, aiming to do just that: represent the stereotyped image of the dominant culture’s male-driven desires, those that reduce womanhood to large, round and perfect breasts, impossible peach-coloured sacs of silicone suspended on a cartoon body. So, I took on the mission of foregrounding and deconstructing these desires, and their innate violence. Later, other readings also emerged: fertility, maternity, generosity, the Venus, the goddess. I embraced all these interpretations, which gradually became indispensable elements in the evolution of the project, as did its censorship in 2014. This was the year that the watercolour Planète des seins, from the series Étude pour habiller une femme éléphant, was withdrawn from a group show of Latin American artists in Montreal. The censorship and the backlash that followed added new layers of meaning to the work: resistance, and the assertion on the part of woman artists that we can and will express ourselves freely on and from our own bodies, our own desires, and our own sexualities. The solidarity of the community involved in the backlash also now forms part of the project—I had made a number of T-shirts printed with the censured image, which my fellow artists wore during several public and private events, photos of which were shared on social media.

I return to my studio. Faced with this ongoing failure, I decide to take a look at myself in the mirror. Here I am, a white woman, quote unquote, or a woman of colour, depending on the context where my body happens to be, and depending on who’s looking at it. Today, whether I’m in Baltimore or Montreal, it’s more or less the same: I’m a person of colour, and now, in front of the mirror, I recognize the different shades of my nipple, this coffee-coloured spot that at one time had the hue of raw meat. I return to the paper. I try to avoid mauves and purples, I try to adjust the greys, and to pay close attention to the shades of brown. The end result is a series of busts the colour and texture of chocolate, wood, or dried nuts. I have to face the facts: my original intention has once again slipped through my fingers.

I don’t think I’m a very good painter, and I don’t think watercolours are especially racist, either. I mention this because, in my search to render darker tones, the paper becomes absorbed with pigment, and its fibres reach a point of maximum saturation. In the process, the essence of watercolour—its transparency—is often lost.

But I’m getting a bit delirious! I can see full well that all my experiments lead to dead ends. I master neither technique, nor colour mixing, nor contrast, nor intensity, nor context.

Returning once again to my watercolour paper, a memory comes back to me, a method taught by my former teacher, Edgar Silva (RIP). One day in class, he had mentioned the name of my lover of the moment (also RIP) in order to demonstrate the usefulness of watercolour painting. The lover in question earned his living by selling large format watercolours of the Cundiboyacense Savanna. It’s with much nostalgia now that I remember him in the fields around the university campus, where we explored watercolour washes and secret-sharing in more direct ways. One of the most beautiful things I’ve ever experienced in this life was the taste of coffee in his mouth. I can recall so clearly the texture of his lips, always moist for me. This detail slips in here, as I am writing from the perspective of an elephant woman; an elephant woman transforms her bedroom into a studio, she sculpts intimacy, learns from her dreams, and gives voice to desire. An elephant woman loves physical matter, and she loves the word SPEAK. I still dream of the watercolour lover and his hair; I visit him in his attic apartment in a neighbourhood called La Soledad. I hear his voice on the phone, it’s becoming fainter and fainter. Then it’s just me talking to myself. And I have the sad impression that I’m about to wake up.

I find myself surprised by all these connections between painting, death, and love. Another loved one who I wasn’t able to mourn. I was already living in Montreal when he was murdered. Might watercolour painting be able to channel my desire for his lost body, this body that I didn’t see, that I didn’t accompany, that I didn’t mourn? Que no duelé. Today, I need to conjugate the word duelo. I experienced the repercussions of that clause that doesn’t appear on the immigration forms, nor the permanent residency forms, nor the citizenship forms: “you will be far away from your loved ones (my mother, my father, my watercolour lover) at the moment of their passing. Your grieving process, if you’re able to carry it out, will be very long.” Later, the only option available to us is pilgrimage. We return to the places where we spent time with the absent loved one: the family home (if it still exists), a street, a park, a mountain, the sea, a song. On a day like today, I wish he was here. I wish we could talk. We would probably talk about painting. We would talk about so many things.

Watercolours, love, illness, death, grief, migration… what’s the relationship between all this and my inability to properly render so-called skin of colour? Perhaps it speaks to the fundamental difficulty of representing the other. Or perhaps, in the end, this technical problem is a metaphor for all the care that needs to be taken when addressing such a delicate issue. I must admit that the reservations I have in approaching this question make me doubt the relevancy of the entire undertaking. At the same time, I’m trying to resolve a problem that arose directly from my practice. What’s more, I feel that this is an inescapable issue for me, particularly as someone from both Montreal and Cartagena.

I return again to the paper, with time, with care, and without expectations. I prepare the wash, I apply the glaze along the long brown puddle, making sure the brush doesn’t touch the paper’s surface. A single colour per layer: I wait for one to dry before adding the next. The result is overly controlled, sterile, and almost illustrative: flattened, puffy globes, crowned with ovals that are supposed to look like nipples. OK, but no. I don’t like it. I don’t like it at all. I try again, now adding other tones. And I find myself once more in the morbid palette of death.

I change locations.

I return to Montreal. I return to the paper and I think back to those lips, to that breath, the coffee breath of the desired and absent lover. A delicious aroma for some, disgusting or banal for others. I wonder if it’s possible to grasp otherness through touch, through the experience of the other’s body, through physical closeness. Or even through a shared struggle? To suffer with someone, to look at them in the eyes, to sit down at their table, to lean back against their knees, to know the smell of their neck, the texture of their hair, to feel the grease of their skin.

Is it possible to love, to understand, to accept, or to welcome through theory alone?

Through the body?

For a fleeting moment, I abandon my watercolour paints to caress the paper with washes of coffee.